Friday, December 07, 2012

The Postman & Always Here, by Ken Liu - IGMS

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Now Available - IGMS - Issue 31

Our cover story, "Inside the

Mind of the Bear" by Rahul Kanikia, is a look at a bear bent on global

domination, presented in the form of a scientific paper. I know, I know, you

see this kind of thing all the time. But I promise you, this one really is

different from all the other scientific papers about Godzilla-sized grizzlies.

Our cover story, "Inside the

Mind of the Bear" by Rahul Kanikia, is a look at a bear bent on global

domination, presented in the form of a scientific paper. I know, I know, you

see this kind of thing all the time. But I promise you, this one really is

different from all the other scientific papers about Godzilla-sized grizzlies. "The War of Peace – Part One"

is the first installment of a novelette by Trina Phillips, part two of which

will appear in issue 32. When humans plant their new town atop the birthing

grounds of an alien race who have planted their offspring seedlings below that

same ground, something has to give.

"The War of Peace – Part One"

is the first installment of a novelette by Trina Phillips, part two of which

will appear in issue 32. When humans plant their new town atop the birthing

grounds of an alien race who have planted their offspring seedlings below that

same ground, something has to give. Doubling as our audio feature for

this issue, "The Flittiest Catch" is tongue-in-cheek look at the

perils of fairy fishing in the open skies. Written by Robert Russell, the audio

version is read by the appropriately gruff-voiced Stuart Jaffe.

Doubling as our audio feature for

this issue, "The Flittiest Catch" is tongue-in-cheek look at the

perils of fairy fishing in the open skies. Written by Robert Russell, the audio

version is read by the appropriately gruff-voiced Stuart Jaffe. Editor, Orson Scott Card's InterGalactic Medicine Show

Thursday, November 08, 2012

Aristocritics: Genre Fiction vs. Literary Fiction

"It is not literature," says the aristocritic. Inevitably, every syllable of "literature" is pronounced.

From time to time, genre writers will shuffle out of their bedrooms, pajama-clad still, and read the aristocritic's words. A defense will conjure upon their fingers. Wordsmiths in grand defense of their chosen medium will summon not just their own prowess, but the screaming hordes of genre-fans to take up arms and strike! For Bradbury, for LeGuin, for Chabon!

Well. I'm not much for war any more. When I was a young writer-- the internet was still a New Thing-- you can bet I was there on the front lines, defending genre. "Genre can too be literature! Yes-huh, it can!"

The older I got, the more I realized-- They're Just Not That Into Me. And the more I realized that there's very little I can do to change that-- trust me, TPing their homes does not work-- the more that genre's insistence that it IS TOO LITERATURE seem like the demands of a petulant teenager demanding attention from an ex. ("If you give me another chance, I know you'll love me this time...")

I think that this is a hard lesson for writers to learn. I crave acceptance and validation, and I think that's true for a lot of us. Part of the reason I write is so that people can see some little piece of me on the page there (distorted, twisted, or made gloriously bright) and say, "Oh! Oh, yes. That's just how I feel, too!" And literary fiction has gravitas and authority-- that's why they have big universities, and libraries, and smoking jackets. So acceptance and validation from one of them is soul-currency. It means a writer has transcended...something.

But transcendentalism is schlock. I learned that by getting older, too. I don't want to transcend: I want to engulf. I want to entwine. I want to enfold.

So, here, genre: have some advice. Stop panting after literary fiction's approbation. If critical acclaim from literary fiction comes, excellent. If it doesn't, forcing the issue won't make either literary mode better.

You, as a literary mode, are not entitled to acceptance or love.

But remember that you ARE loved by those who matter most: readers.

In the end that's what it comes down to: from a certain sense, base populism. The greatness of a story, I believe, is in how broad its audience is, and how deeply the tale pierces their souls. Concentrate on that-- casting wide nets of evocative story-telling-- and let the aristocritics get back to their tea.

Monday, November 05, 2012

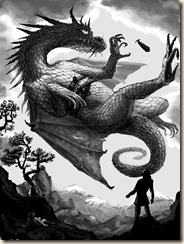

Dragonslayer—Nathaniel Lee

My friend David Steffen wrote a piece called "The Quest Unusual" for the PodCastle flash fiction contest. His story was a humor piece,  featuring a dragon in armor asking oblivious local peasants if they'd seen any dragons around, with the punch-line being the rural man's remark that there was no such thing as dragons. I couldn't get the image of a dragon-who-is-a-knight out of my head, especially once I realized that he would logically have to be looking for a knight-who-is-a-dragon, just for symmetry. I started out writing just a 100-word sketch for Mirrorshards, but that wasn't enough to exorcise the idea. I didn't want to "waste my time" writing an entire story because I felt like I was just riffing on David's concept. However, at the time, I was under a self-imposed demand to write at least one full short story every two weeks for a full year, so I finally just gave up and went for it, figuring I'd keep it for myself if it turned out rubbish.

featuring a dragon in armor asking oblivious local peasants if they'd seen any dragons around, with the punch-line being the rural man's remark that there was no such thing as dragons. I couldn't get the image of a dragon-who-is-a-knight out of my head, especially once I realized that he would logically have to be looking for a knight-who-is-a-dragon, just for symmetry. I started out writing just a 100-word sketch for Mirrorshards, but that wasn't enough to exorcise the idea. I didn't want to "waste my time" writing an entire story because I felt like I was just riffing on David's concept. However, at the time, I was under a self-imposed demand to write at least one full short story every two weeks for a full year, so I finally just gave up and went for it, figuring I'd keep it for myself if it turned out rubbish.

Two days and seven thousand words later, with the story largely in its present form (I am both a binge writer and an incorrigible  pantser), I realized that the concept *really* had legs. I sent the manuscript to David; because the story was largely inspired by his own, I didn't want to submit it anywhere without his permission. Initially, David was (understandably and thoroughly justifiably, I think) reluctant, and he told me I'd have to trunk the piece, as I'd expected. A few days later, however, he changed his mind, and asked only that I wait until he'd sold his flash fiction story. (He says he was worried that a glut of dragons-that-are-knights would drive demand down, making it a harder sell; me, I think you can never have enough dragons.) As you've likely guessed, David's piece sold quite quickly (you can read it at Daily Science Fiction's permanent archive), and so here we all are today.

pantser), I realized that the concept *really* had legs. I sent the manuscript to David; because the story was largely inspired by his own, I didn't want to submit it anywhere without his permission. Initially, David was (understandably and thoroughly justifiably, I think) reluctant, and he told me I'd have to trunk the piece, as I'd expected. A few days later, however, he changed his mind, and asked only that I wait until he'd sold his flash fiction story. (He says he was worried that a glut of dragons-that-are-knights would drive demand down, making it a harder sell; me, I think you can never have enough dragons.) As you've likely guessed, David's piece sold quite quickly (you can read it at Daily Science Fiction's permanent archive), and so here we all are today.

--Nathaniel Lee

Friday, October 26, 2012

Write What You Want—Eric James Stone

For several years, the Codex Writers forum has held a contest called "Weekend Warrior." For five straight weekends starting in January, several writing prompts are posted on Saturday morning, and contestants must submit a flash fiction story based on a prompt  by Sunday night. Last year, on the final weekend, the prompt-giver included a very open-ended prompt: "Write anything you want."

by Sunday night. Last year, on the final weekend, the prompt-giver included a very open-ended prompt: "Write anything you want."

Naturally, I had to find a way to put a twist on that prompt, so I decided to write a story about writing what you want. And because I sometimes like to experiment with style and form while writing flash fiction, I decided to intersperse things people wanted between each paragraph of the main storyline.

I'm not sure exactly how I came up with the plot, but it was probably something similar to this train of thought: OK, so people write what they want on a piece of paper, and someone does what? Grants the wish? Too straightforward. How about he takes that want away? That might work. Why does he do it? Because sometimes what we want gets in the way of our own happiness. So he's a good guy for doing this. But where's the conflict? What if someone comes in with a want that shouldn't be forgotten? And at that point I had the basic plot.

Most of the stories I write tend to be about people who face a problem and overcome it by the end. This story is not like that. I did write an alternate ending where the main character tricks the girl's father into writing something so that the magic could be used against him, but after writing it I felt that ending trivialized the problem of sexual abuse. And I don't think that's something that should be trivialized.

problem and overcome it by the end. This story is not like that. I did write an alternate ending where the main character tricks the girl's father into writing something so that the magic could be used against him, but after writing it I felt that ending trivialized the problem of sexual abuse. And I don't think that's something that should be trivialized.

--Eric James Stone

Friday, October 19, 2012

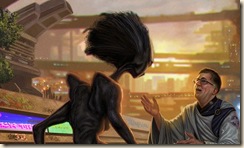

Constance’s Mask- Nick T. Chan

This story emerged directly from my writers of the future volume 28 story, The Command for Love.

My first draft of that story was an abysmal attempt at an artificial intelligence story, featuring lots of incomprehensible jargon about Turing Tests and Chinese Rooms. It didn’t work . I wanted to meet the deadline for the quarter as I’d just decided I was going to enter every quarter of Writers of the Future until I won or died of old age.

intelligence story, featuring lots of incomprehensible jargon about Turing Tests and Chinese Rooms. It didn’t work . I wanted to meet the deadline for the quarter as I’d just decided I was going to enter every quarter of Writers of the Future until I won or died of old age.

I had no idea how I was going to re-write it until a conversation with another writer, Jennifer Campbell-Hicks, sparked the idea that I should re-write it in a different genre. I was reading Gra Linnaea’s Writers of the Future volume 25 story A Life in Steam at the time, so the decision was made for me: Steampunk (luckily Fifty Shades of Gray wasn’t around at the time).

After writing the story, I sat back and realised two things: I enjoyed writing in the world I’d created and I knew nothing about the Victorian era where a lot of steampunk draws its inspiration. I wanted to explore the world further and I wanted my explorations to fit comfortably within the steampunk genre.

I started to read about the Victorian-era. Because I’m lazy, my research petered out after a few days, but one of the books I read was The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde by Neil McKenna. It was a fascinating and disturbing read. By any standard, Oscar Wilde was a sexual predator, but the dark side of the Victorian era was the intertwining of sexuality and class. By the time he’d accepted his sexuality he was doing to young underclass men what many (or even most) respectable Victorian gentlemen did to young underclass women; he exploited them for his own pleasure (and some of them exploited him back via blackmail). He was a complicated and courageous man who was also a selfish monster. Like many martyrs for a cause, he wasn’t necessarily an admirable man on a personal level but he was a talented monster who was willing to sacrifice everything for his beliefs.

Oscar had an unhappy marriage to Constance Lloyd. He’d married her out of genuine friendship, a mistaken platonic love, ambition, and the desire to “cure” himself of what was socially unacceptable. Constance Lloyd was a pretty young woman who was tremendously psychically scarred from a difficult upbringing. It wasn’t hard to make Constance the centrepiece of the story and make her scarring physical.

her out of genuine friendship, a mistaken platonic love, ambition, and the desire to “cure” himself of what was socially unacceptable. Constance Lloyd was a pretty young woman who was tremendously psychically scarred from a difficult upbringing. It wasn’t hard to make Constance the centrepiece of the story and make her scarring physical.

As time went on, Oscar became more determined to be open about his sexuality and to use his art as an expression for that sexuality. Society be damned; he was what he was and he refused to back down from his principles even when it was the smarter thing to do.

All that went into a story set in the same world as The Command For Love, which eventually became Constance’s Mask. By the time Constance’s Mask was in its published form, a lot of the common-world story had been stripped out for reader comprehensibility, but the core remained. It was still about blackmail and masks, the discrepancy between our public and private selves, genius and monsters, the power of stories to both enslave and liberate and bringing your true self into the light.

-- Nick T. Chan

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

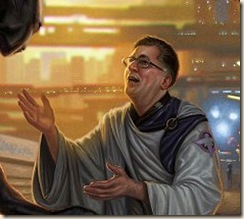

Sojourn for Ephah—Marina J. Lostetter

Sojourn for Ephah is really a tale of two characters, and each came about in their own way.

I have to thank my brother for Ephah. If we hadn’t been having our  worst fight since we were kids my neurons might not have fired just right, and Ephah might never have been.

worst fight since we were kids my neurons might not have fired just right, and Ephah might never have been.

No need for all the details, but essentially we both said some bad things that had nothing to do with what the fight was about. I was so angry I began wringing my hands while chanting, “Calm down. Just calm down.” Almost like a prayer. But I wasn’t speaking to a deity, I was speaking to myself.

I began to wonder under what circumstances a being might pray to itself. And thus Ephah--along with her brief stint in a foreign universe--was born.

Thomas, on the other hand, was a direct reaction to what I’d been reading. It seemed like every spec-fic story containing a monotheistic religious leader wound up the same way--with the individual denouncing their god, fleeing from faith, and in a few cases, killing themselves. All because some new scientific discovery clashed with their dogma. I think this is an unrealistic--and now, rather stereotypical--take on people of faith.

Thomas, on the other hand, was a direct reaction to what I’d been reading. It seemed like every spec-fic story containing a monotheistic religious leader wound up the same way--with the individual denouncing their god, fleeing from faith, and in a few cases, killing themselves. All because some new scientific discovery clashed with their dogma. I think this is an unrealistic--and now, rather stereotypical--take on people of faith.

Human beings don’t tend to let their worlds come crashing down that way. Someone of real conviction (religious, political, moral, etc.) tends to respond to new, contradictory information in one of two ways--either they deny it, or they incorporate it.

What happens when you have a political conversation with someone whose views strongly oppose yours? What happens when you present facts that clash with their beliefs? They either explain how those ‘facts’ are nothing of the sort, explain how those facts actually make their point, or they accept the facts and let their beliefs evolve. It’s doubtful, I think, that they’ll do a one eighty--denouncing all of their pre-conversation convictions--or crumble into suicidal oblivion.

whose views strongly oppose yours? What happens when you present facts that clash with their beliefs? They either explain how those ‘facts’ are nothing of the sort, explain how those facts actually make their point, or they accept the facts and let their beliefs evolve. It’s doubtful, I think, that they’ll do a one eighty--denouncing all of their pre-conversation convictions--or crumble into suicidal oblivion.

New scientific principles aren’t likely to be seen by a religious person as a tragedy there’s no escape from, because that’s just not how people are built.

So, I wanted to write a character that embodied the real-world tendency to incorporate new information, and came up with Thomas (I suppose I also wrote a character that embodies the rejection aspect: Bishop Krier). Thomas is intelligent and open minded, and never backs away from his faith simply because he’s learned something new.

I think Thomas and Ephah are a perfect philosophical and psychological match, and I hope you enjoy their story.

--Marina J. Lostetter

Monday, September 17, 2012

The Butcher of Londinium—J. Deery Wray

I came up with the initial idea for "The Butcher of Londinium" while  skimming through a Jack the Ripper book for information on police procedure in 1880's London. At the same time, I was watching the first season of Spartacus. The two merged in my head, and I began to toy with the idea of a serial killer, sentenced to die in the arena, who made a deal with a Lanista to survive. Could the gladiators come to accept him? If so, why? What about a man who'd lost everything because of him?

skimming through a Jack the Ripper book for information on police procedure in 1880's London. At the same time, I was watching the first season of Spartacus. The two merged in my head, and I began to toy with the idea of a serial killer, sentenced to die in the arena, who made a deal with a Lanista to survive. Could the gladiators come to accept him? If so, why? What about a man who'd lost everything because of him?

Since I had Jack the Ripper in mind, I set the story in an 1880's alternate version of England where the Romans had never left. Surgery gave me a link between the first and second question, as well as a reason the Lanista might be willing to deal.

Still, it didn't seem like quite enough to me. I needed something more, an emotional center that could tie everything together, and put the two main adversaries, the serial killer and the wronged man, in conflict not just because of past events, but also in terms of present ones.

Still, it didn't seem like quite enough to me. I needed something more, an emotional center that could tie everything together, and put the two main adversaries, the serial killer and the wronged man, in conflict not just because of past events, but also in terms of present ones.

So Stolo was born.

Once I had Stolo, I knew I had all I needed to start the story. But then I hesitated. I began to doubt if I could pull off a first person story from the point of view of a serial killer. Maybe I should just move on to some other, easier idea? I decided to go ahead with the story anyway as I realized I'd fail harder by not trying at all than by trying and not pulling it off.

I'm glad I did.

-J. Deery Wray

Tuesday, September 04, 2012

The Flower of Memory—Michael Haynes

This story was written not long after I returned to writing from one of many long hiatuses. At that point, I was experimenting with all sorts of ways of finding story inspirations. One of these, which only lasted a very brief while, was to have visitors to my blog vie to present me with the most interesting prompt they could find for a short story. I'd then write the story and present it on my blog. The idea didn't really catch on and this series on my blog ended after two iterations.

many long hiatuses. At that point, I was experimenting with all sorts of ways of finding story inspirations. One of these, which only lasted a very brief while, was to have visitors to my blog vie to present me with the most interesting prompt they could find for a short story. I'd then write the story and present it on my blog. The idea didn't really catch on and this series on my blog ended after two iterations.

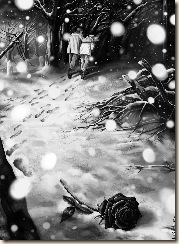

For the second iteration, I was given an image of a rose against snow. I played with a couple of story ideas. For my blog, I wrote a story about college romance -- the rose here being a peace offering discarded by its recipient.

But the imagery stuck with me and the other idea I'd had, about a flower in a ruined greenhouse and a landscape prematurely gone to winter, didn't want to be cast off. The J. M. Barrie quote used in the story is one I'd come across when considering epigraphs for a now-trunked story about a memory-recording service. The image and the quote came together to create this story, which I'm very glad to have seen published in Intergalactic Medicine Show.

-- Michael Haynes

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Riding the Signal—Gary Kloster

So, monkeys.

I don't have a problem with monkeys. I don't want one, but then I firmly believe that you should never have a pet with thumbs. And  while the flying monkeys in the Wizard of Oz freaked me out, but that was a long time ago, and I've recovered. Monkeys are fine. They're fun to watch at the zoo. Some have mustaches, and that's great.

while the flying monkeys in the Wizard of Oz freaked me out, but that was a long time ago, and I've recovered. Monkeys are fine. They're fun to watch at the zoo. Some have mustaches, and that's great.

I'm cool with monkeys.

The first sci-fi short story I wrote had a monkey in it. She was the protagonist's romantic interest. Maybe I should unpack that. She wasn't really a monkey, you see, she was a biologist on a spaceship who had uploaded her brain into a computer along with the rest of the crew, and the monkey body was just a VR thing she was doing to… Well, it gets complicated.

Science fiction's like that sometimes.

Anyway, I had a monkey. Not an evil monkey, though. She was just being a monkey to annoy my protagonist. The guy that liked her. That was part of the reason, at least. Like I said, complicated. So maybe that character had a thing about monkeys.

But that was just something about him.

Recently, I wrote another story with a monkey in it. A cute, helpful, friendly monkey, who wanted to help my protagonist and his family out. Maybe. That part's unclear. It's definitely a monkey though. An alien monkey, who is possibly (probably) a robot, but not evil. Maybe.

Having the alien look like a monkey, that made sense for the story. It was just camouflage. No deeper meaning.

Having the alien look like a monkey, that made sense for the story. It was just camouflage. No deeper meaning.

Now this story, Riding the Signal. Another monkey. An evil robot monkey, with sharp claws, a skull face, and a mouth full of terrifying laughter and poison. A monkey that hides and stalks, tortures and kills.

So maybe I do have a thing about monkeys. Maybe my cousin had one of those wind-up cymbal banging monkey toys that would just stare and smile at me whenever I visited. Maybe cute moustaches can't quite cover long, sharp teeth. Maybe I've spent too much time imagining tiny little hands with tiny little thumbs easing locks back, silently turning doorknobs, creeping across dark floors… Yeah, okay, monkeys kind of freak me out.

Still. Three stories about monkeys, and every one has sold.

Maybe I should think about that. Or maybe not.

Thinking about wind-up clockwork flying monkeys isn't going to help me sleep at night.

--Gary Kloster

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

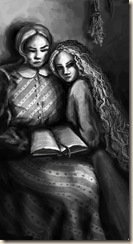

Dark and Deep—Holli Mintzer

I started this story a couple of times. I knew I wanted to write  something about backcountry witches, and about the relationships between sisters and mothers and daughters, but it took a few tries to figure out how to set up my narrator's situation in a way that grabbed me. I wanted my narrator to be in a situation that, to her, is perfectly ordinary, but hint at the unsettling details of her life without giving to much away.

something about backcountry witches, and about the relationships between sisters and mothers and daughters, but it took a few tries to figure out how to set up my narrator's situation in a way that grabbed me. I wanted my narrator to be in a situation that, to her, is perfectly ordinary, but hint at the unsettling details of her life without giving to much away.

I deliberately left the exact era vague-- the only clue as to time period is the tintype, which places them sometime after 1853. The sisters and their mother are far from civilzation, and they're pretty old-fashioned anyway. Their magic is a mix of medicine and superstition and pure willpower; there's probably fancy city wizards with strings of letters after their names in this world, but in the woods it comes down to what you can do with the tools at hand.

One of the things that started the story, oddly enough, was the idea of a helpful zombie. Zombies are the servants of magical practitioners in some traditions, but I didn't want that exactly. I wanted someone who was too stubborn to stay dead, and so dedicated to the living she'd left behind that she keeps going as long as she can. That mixed itself up with my thoughts about old-timey witches, and then I had a story.

a helpful zombie. Zombies are the servants of magical practitioners in some traditions, but I didn't want that exactly. I wanted someone who was too stubborn to stay dead, and so dedicated to the living she'd left behind that she keeps going as long as she can. That mixed itself up with my thoughts about old-timey witches, and then I had a story.

--Holli Mintzer

Monday, August 06, 2012

For Lenore—Kenneth Kao

Ah, the story behind the story. Well, lucky for me, there's a story behind "For Lenore" that I don't have to exaggerate one bit. And it's crazy.

It all began with a fight with my wife.

See, my wife has this irresistible urge to take things, even if she's  entitled to them. Usually, she takes things in the form of too many napkins at a restaurant or a roll of toilet paper from a public bathroom, but when it comes to construction equipment and road signs...

entitled to them. Usually, she takes things in the form of too many napkins at a restaurant or a roll of toilet paper from a public bathroom, but when it comes to construction equipment and road signs...

It always goes down to this: she sees a cone on the road; she wants to take it; I'm the one driving; she leans out to grab it; I swerve away.

Or, we're walking and before I know it she's carrying it with her, or wearing the cone as a hat.

Well, one night, I come home to find her with a sign. Not just a sign, but a big neighborhood corner sign sitting in the middle of the living room(see attached picture). She's the cutest thing in the world, so saying no to her--especially after she has her hands on something--is akin to taking an ice cream triple-decker cone from a kid.

But--I'm the stiff, "boring", the ethic driven guy in our relationship. She's the naughty, playful, and interesting one. I always have to tell her, "No, return what you took, I love you and you're cute as hell but we can't steal." When she puts the thing back, the look she gives me always makes me feel guilty as hell.

Anyway, I played along for as long as I could. I think she was testing me to see how far she could push it before I broke, but hours later and she wasn't showing any intention of putting the sign back.

I panicked, a little, and then a lot as she kept shaking her head and hugging it as reply to my prompts--

I snapped.

I told her it was STEALING, and no matter what, we had to put it back gosh-dang-it. I yelled at her. And made her feel bad. And then I felt bad. And she put the sign back outside where she'd found it and went to bed all sullen and quiet.

gosh-dang-it. I yelled at her. And made her feel bad. And then I felt bad. And she put the sign back outside where she'd found it and went to bed all sullen and quiet.

She didn't say a word to me the rest of the night.

So, 3am and unable to sleep, I decide that I'm going to my clinic--I have patients early the next morning. I'm still seething, mostly from my own guilt, but also angry because I felt like, "Why the heck did you have to push me so far? You knew exactly what you were doing!"

...But on the drive to the clinic. There's this construction zone that's been going on for months. There are these THINGS. Big, orange, trash can sized reflector things that I've only recently learned are called "tire ring drums.”

They are massive and round and heavy(25 pounds of unwieldy-ness). And the thought crosses my mind: What if? It would be epic. It would be the can't-top-this move. It'd be romantic! She'd forgive me, and no matter what the moral consequence is--I owe it to her for yelling, right?

So, in my dress clothes, where a long stretch of road has no lights, I jump out of my car and pop the trunk and lug one of those around to throw into the trunk of my Camry.

Turns out it doesn't fit. I think they were designed not to fit.

After running around the car and trying the back door, the front door, any way to get the thing in while hoping that no one comes driving down the road, I put it back and get in my car and give up.

My epic plan has failed. My apology will never come through. And if I steal something else, a mere cone, let's say--I would always know what could've been, and it wouldn't really mean that much since she's stolen cones before. Or at the very least, it wouldn't mean what a super-sized tire ring drum would mean.

So I get to the clinic and I write, in my frustration, "For Lenore."

Originally titled: "The Bomb is Greener on the Other Side."

You could tell I was in some sort of mood.

The next day I treat my patients, but I can't get the idea out of my head. I vividly see how sad my wife looked after I yelled at her.

head. I vividly see how sad my wife looked after I yelled at her.

She was only being playful. So I visualize the size of the tire barrel thing and my tiny Camry--Why couldn't I have driven the Jeep!--and I purposefully stay late at the clinic.

On the way home, it's only slightly after dark around 8pm, I find a spot and go running out again. I know a car's gonna come down the road any second because I've been sitting on the side of the road for several minutes, waiting for that brief window of opportunity. I throw open the passenger side door and drop the seat back. I seize one of the tire ring drums and put it into the passenger seat head first. It's bottom touches the ceiling. But it worked, and perfectly. And then I'm off. On my home with a dirty but shining, orange reflector thing next to me.

I imagine what a cop might do if he saw me. But you can buy these online, right? That's what I told myself, at least.

I get home, and my wife's making dinner, and I drag it in.

Her expression was everything I could've hoped for.

Gotta say, I felt like a stud. And don't worry about the Tire Ring Drum, I'm the ethical guy, remember?

--Kenneth Kao

Thursday, August 02, 2012

InterGalactic Medicine Show, Issue 29

Welcome to Issue 29 of IGMS. There's a drought across much of America this summer, but there's no shortage of good reading here at IGMS.

Our cover story, "The Butcher of Londonium" is a splendid alternate history where the Roman Empire survives long enough to meet Jack The Ripper, who is pressed into service as doctor to the gladiators who fight and live and die in the city of Londonium. Not quite your father's Olympic Games, eh?

Our cover story, "The Butcher of Londonium" is a splendid alternate history where the Roman Empire survives long enough to meet Jack The Ripper, who is pressed into service as doctor to the gladiators who fight and live and die in the city of Londonium. Not quite your father's Olympic Games, eh?

Next up is Gary Kloster's "Riding the Signal." When a secret group of high-tech mercenaries get attacked with a variant of their own long-distance animal-robot devices, their only chance of survival rides on two things they've never had to do before: work together, and get their own hands dirty.

Doubling as our audio feature for this issue, "Cloudsinger" is the  lyrical story of young teller of tales who goes to great lengths to get the details right, and the special opportunities such attention to detail brings. Written by Jared Adams, the audio version is read by our regular audio-contributor Tom Barker.

lyrical story of young teller of tales who goes to great lengths to get the details right, and the special opportunities such attention to detail brings. Written by Jared Adams, the audio version is read by our regular audio-contributor Tom Barker.

"Dark and Deep" by Holli Mintzer brings us the lives of a pair of young witches who live deep in the woods, far from the local towns and villages for many good reasons, not the least of which is their mother, who protects them with the passion and determination that only a mother can bring.

And last but certainly not least, we have a pair of short-shorts. Since they're both under 1,000 words we decided two was better than one, to ensure everyone got their money's worth. The first is Ken Kao's somewhat surreal SF tale, "For Lenore," while the second is Michael Hayne's post-apocalyptic "The Flower of Memory." I'd describe them to you, but they're short-shorts, remember? In the time it would take me to describe them, you could have already read them.

So what are you waiting for? Time to dive in and start reading . . .

Edmund R. Schubert

Editor, Orson Scott Card's InterGalactic Medicine Show

P.S. As usual, we've collected essays from the authors in this issue and will post them on our blog (www.SideShowFreaks.blogspot.com) Feel free to drop by and catch The Story Behind The Stories, where the authors talk about the creation of their tales.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

The Curse of Sally Tincakes—Brad R. Torgersen

"The Curse of Sally Tincakes" began life as a workshop story in  Lincoln City, Oregon. It is the fraternal twin of my Nebula and Hugo award nominated cover story, Ray of Light, which appeared in the December 2011 issue of Analog Science Fiction & Fact.

Lincoln City, Oregon. It is the fraternal twin of my Nebula and Hugo award nominated cover story, Ray of Light, which appeared in the December 2011 issue of Analog Science Fiction & Fact.

For Tincakes, our assignment was to write a story about curses. That was it. Just, curses. Well, I knew going in that the bulk of my compatriots were going to hit it from a fantasy angle: sorcery, witchcraft, occult, voodoo, et cetera. Me being me, I immediately thought -- not of demonic or mystical curses -- but of sports curses. The Curse of the Bambino, The Curse of the Black Socks, The Curse of Muldoon, et cetera. I also wanted to write a story that would be sufficiently science-fictional to sell to the editors who were familiar with and had enjoyed my previous work.

So, my thoughts turned to racing.

Now, the idea of the futuristic or "space race" is a recurrent concept in SF -- the pod racing sequence from the first of the three Star Wars  prequels being a notable high-profile example. Contests of speed are as old as human civilization, so it stands to reason that we'll still be having them long after we've become a truly interplanetary people.

prequels being a notable high-profile example. Contests of speed are as old as human civilization, so it stands to reason that we'll still be having them long after we've become a truly interplanetary people.

And as long as we have races, I suspect we will have racing curses too.

The story itself grew from this assumption.

To tell it classically, I knew I needed a young, somewhat brash protagonist, and an older, grizzled veteran to act as both mentor and foil. I also needed to come up with the curse itself. Racing, like boxing, has a history of parading beautiful women in swimsuits for the delight of the (assumed, mostly male) crowds. I decided to make my story about a curse imposed by a bikini girl done wrong -- which seemed to dictate that my protagonist would also need to be a woman, because when women take on other women it can be a practically evil thing to behold.

Of course, Jane Jeffords doesn't believe in the curse. Why would she? She's a child of her (future) era. Curses? Hah! What a load of crap.

Thus the story unfolded.

The workshop's reaction was generally positive. Dean Wesley Smith in particular seemed to like it. "This is NASCAR on the moon!" he exclaimed. Send it out, he said. Right away.

I did not expect it to get the cover spot in the 28th issue of Orson Scott Card's Intergalactic Medicine Show. Nor did I expect it to  garner such a fantastic piece of artwork. The digital painting by Nick Greenwood is like a photograph from my own mind; he captured the signature image of Jane -- riding her Falcon – that perfectly. It's truly one of the great pleasures (of being a writer) being able to see my words translated through the creative lens of talented illustrators. Nick's piece in particular really knocked my socks off. Is he telepathic? I wonder.

garner such a fantastic piece of artwork. The digital painting by Nick Greenwood is like a photograph from my own mind; he captured the signature image of Jane -- riding her Falcon – that perfectly. It's truly one of the great pleasures (of being a writer) being able to see my words translated through the creative lens of talented illustrators. Nick's piece in particular really knocked my socks off. Is he telepathic? I wonder.

On a deeper level, "The Curse of Sally Tincakes" deals with rejection and loss, as well as the will to persevere: despite the odds, despite setbacks, despite people telling you to quit when what your heart wants is to go all the way. I've said it before in other spaces that I am not a fan of downer stories, trendy and "realistic" as they may be. And while Tincakes doesn't have a Hollywood ending per se, I like to think the message is clear: the real difference between winning and losing, is having the courage to never give up.

Of course, I have to thank editors Scott Roberts and Edmund Schubert for their enthusiasm and insight. It's often said by professionals that no story is perfect, just finished. Or is it that no story is finished, simply abandoned? Ed's comments were thus: something's dangling there at the end, we need more 'oomph' to make this thing matter. Redressing the details leading up to the ending, I went in a direction Ed didn't expect. And with a little banging and cutting, it came out rather good. Good enough, anyway, for IGMS standards. Which is plenty good enough for me!

It's been terrific fun seeing my story headlining IGMS for the last couple of months. And I will treasure the Nick Greenwood artwork forever, as a stupendous realization of my character Jane Jeffords at the height of her personal drama: fists gripping the control bars, calves and legs clamped to the sides of the Falcon, the rear engines slewing dramatically as Jane's competitors jockey in the distance. And of course, Sally herself overseeing it all, her Hollywood grin belying a sinister intent. Marvelous. Simply marvelous. Thank you Nick, thank you Scott, thank you Edmund.

--Brad R. Torgersen