When one looks at the plethora of gaming systems out there, one notices LOTS of castles. And dragons. And hermaphroditic denizens of forests, lakes, and swamps. Fantasy worlds are more than a staple—they’re practically the TEMPLATE.

Wizards of the Coast’s d20 Modern offers relief from the hordes of elves, gnomes, halflings, and so forth. It brings the player’s party up to the age of gunpowder and beyond.

Where both Iron Heroes and D&D 4e (and all previous iterations of D&D, to an extent) are best served by players choosing a niche for their character to fill, the d20 Modern system encourages players to allow their characters to fill multiple roles. In a sense, it is the system that allows for Renaissance Men; it practically requires characters to branch out from their initial concept. Where multi-classing is an option in other systems, sticking with a single class in d20 Modern can seriously crimp your character’s growth and ability to survive in the Brave New World.

d20 serves both combat and non-combat situations equally well. Its capability to handle non-combat situations is SO marked and so impressive, it quickly usurped standard D&D (and 3.5e variants) as my preferred system. Flexibility is the name of the game, and d20 Modern plays it really, really well. It has to: d20 Modern is meant to cover an enormous range of technological innovation, from gunpowder to gunships to starships. And more! Want to introduce contemporary fantasy or horror to your gaming group? d20 is your system. Elves with laptops! Cyberpunk, Steampunk, Jungle-punk! All can fit into the gears of the d20 Modern machine.

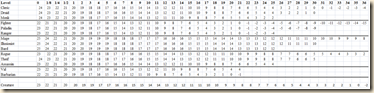

d20 Modern emphasizes skills in order to maintain this flexibility. Skills are generally defined enough to allow for translation to different ages—Craft (Mechanical) can be used to build a catapult as well as a new FTL drive for a starship, depending on the setting. Navigation can be used to read computer output to navigate star-ways as well as to read the stars to navigate a sailing vessel. There are a LOT of skills characters have to draw on, too: the sheer number of skills available might overwhelm those players who are more habituated to skill-lite systems.

d20 Modern has a bevy of feats available to characters in general; but also offers several feat trees within classes. For example, the Charismatic class has three paths: Leadership, Charm, and Fast-talk. Each path has three feats which are acquired as the character advances; each path is designed to use the class’ prerequisite (Charisma) in a different way. The leader may use his feats to help coordinate team-members in battle; the charmer may use his feats to boost his ability to be convincing outside of combat; the fast-talker may be able to better con his targets. While this feature may seem designed to drive characters into a niche, the skill system and the need for multi-classing serves to offset that.

Sometimes the d20 Modern system gets a bit too big for its britches, though. The rules can get a bit hairy and complex. Case in point is the wealth system. Gone is the relatively simple days of gold pieces; instead, wealth (as written in the rules) is a function of a die roll, occupation, level, and an equation whose formula I don’t remember right now. :) Spent wealth is accumulated over a given period of time, but (barring a successful bank robbery or inheritance, or windfall of some sort) you’re not likely to exceed your initial wealth rating. It was confusing enough for my Game Master to declare it utterly broken, and to use home-brew wealth rules.

In my experience, d20 Modern heroes are a bit more fragile than their fantastically empowered peers. There is no divinely-empowered Walking Medical Kit; healing takes time and rest. Of course, there ARE rules that permit instantaneous healing, ala ‘Cure Light Wounds’ spell, but I didn’t play THOSE games.

The extent of customization available in d20 Modern is such that it’s probably not the best system for brand new role players. From what I understand from my GM, ditto for new Game Masters. But if you’ve cut your teeth on swords and dragon’s talons; if you’ve got an eye on that far distant land of the future; if you’re prepared to step out of the dark ages into the land of Enlightement, Reason, and Gunpowder, give d20Modern a shot.

With that, let me close with this: unlike 4e and Iron Heroes, you can find much of the source material for d20 Modern for free and online HERE.

Next time: no d20, no d10, no d8 even. Embrace your FATE.